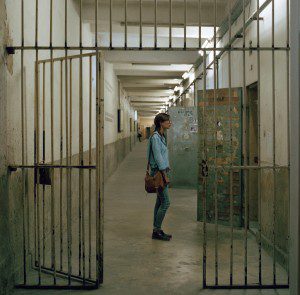

Broken Like Me: Volunteering in a Prison Fellowship Ministry

Written by Alfie Lim, Singapore

“I am thankful I got caught because otherwise I would have just continued what I was doing.”

“Actually, we can be thankful that we have food and a roof over our heads.”

These are snippets of what inmates have shared with me in my short time volunteering with a prison fellowship ministry.

Sometime in 2020, shortly before Covid-19 hit, I had borrowed and read Jason Wong’s Trash of Society: Setting Captives Free. The book traces the author’s journey of faith and work, including his substantive contributions to the Yellow Ribbon Project and his years in the Singapore Prison Service. It revealed to me a compelling alternative vision of hope and flourishing even in the midst of what most people would consider to be a terrible state of affairs—imprisonment.

After some prayer and reflection, I signed up as a volunteer with Prison Fellowship Singapore to support their work, despite being relatively young compared to the typical volunteer in this ministry.

Even though I have some understanding of the criminal justice system in Singapore, I was unsure about what to expect in my first few Christian counselling sessions with the inmates. This was not helped by the fact that on most occasions, I would be the youngest person in the room. Thankfully, with the guidance of my buddy (who is much more experienced and winsome than I am), I grew to become more familiar with the setting and expectations of prison ministry.

The sessions typically comprise three segments—worship, Bible study, and discussion, where time permits. Most of the inmates who attend either grew up in a Christian background or came to Christ during their time in prison, and attend these sessions by choice. Ordinarily, different components of the session are co-led by the inmates and the volunteers depending on availability.

One of the things that struck me from the first few sessions was the depth of knowledge and earnestness of the attendees. The questions they asked, along with the frank discussions and sharing, showed that they not only possess an excellent grasp of the Word, but also a firm belief of its authority over their lives. I do not think I could profess an equal level of commitment and faith in many of those respects.

Two things stood out as I reflected upon my experience thus far.

The first reflection is that these inmates I met were similar to me in many ways—most notably and crucially, sinful and broken. Without delving into the details, it became awfully clear to me (especially in moments of quiet and private reflection) that I too am beset by sin and temptation of all kinds. It follows then that any foundation for moral high ground quickly vanishes, and as the saying goes, but for the grace of God, we go.

None of this should be misconstrued as a flippant view of crime and punishment. It is undeniable that these inmates have to contend with the grave consequences of their crimes, which often have rippling and long-lasting effects on the immediate victim(s), the victim’s family, and the inmate’s own family, among others. But even without going through the complex terrain of criminology, my view is that as Christians, we should be slow to cast the proverbial stone at any of these inmates (or anyone for that matter).

Moreover, as a society, we should not lose sight of the importance of rehabilitating and reintegrating offenders. The Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon emphasised the same on several occasions, including his recent keynote address at the Sentencing Conference 2022:

…rehabilitation and reintegration are crucial to reducing recidivism and thus preventing crime, which is a core goal of the criminal justice system. Rehabilitation tackles the root causes of criminality, which if not addressed can give rise to repeated cycles of offending. And reintegration ensures that upon completion of their sentences, discharged offenders have a chance to build a new life and to break away from undesirable associations and habits that can lead them to reoffend.

… justice and human dignity demand that once an offender has repaid his debt to society by serving his sentence, he should be allowed to re-join the community, and not be kept outside of it. Ex-offenders must be encouraged to resume the rights of full citizenship, and to chart a life free from the shadow of crime. [emphasis added in italics][i]

I am reminded of the fundamental truth of the imago dei and the words of Timothy Keller from his book The Meaning of Marriage: “The gospel is this: We are more sinful and flawed in ourselves than we ever dared believe, yet at the very same time we are more loved and accepted in Jesus Christ than we ever dared hope.”

My second reflection is that we are called to seek the shalom or peace of the community we live in. This calling is outlined in Jeremiah 29:1-7. The Israelites were in exile in Babylon but instead of “rescuing them”, God instructed them to build houses, plant gardens, take wives and have children, among other things (vv. 5-7).

The common thread here is that the various acts involves embedding or committing oneself to a place. Jeremiah goes on to urge the Israelites to seek the welfare of Babylon for therein, they will find their welfare, before (famously) presenting God’s promise that He has a plan and future for those in exile.

We, too, are sojourners here for a finite span of time. Culture often peddles the dubious narrative that idolises fleeting relationships, frenetic activity, and new-fangled interests over faithful, consistent “day-in, day-out” commitment. I suspect this narrative has a particular appeal with younger people.

Jeremiah instead encourages us to sink roots in our communities even where it is difficult. A significant part of this, in my view, entails looking at the felt needs in our community, and discerning where and how we can each make a contribution to its welfare, particularly in respect of the forgotten and downtrodden.

It is sometimes tempting to think of God’s calling as something extraordinary or dramatic. However, if we pay closer attention, there are many ordinary, simple but no less powerful ways of glorifying God. I trust that whatever your contribution, you, too, will be ministered to in the process.

Alfie Lim is a 29-year-old lawyer and serves in the Youth Ministry at Christalite Methodist Chapel.

This article originally appeared in the Oct 2022 Issue of Methodist Message. This version has been edited by YMI.

[i] Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon: Keynote address delivered at the Sentencing Conference 2022 (1 November, 2022)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!