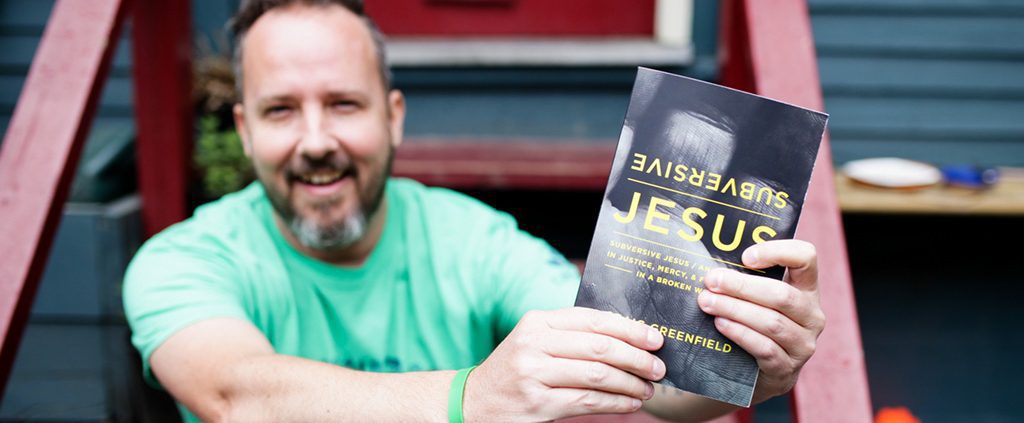

Craig Greenfield: Family in the slums and urban fringes

Seven-year-old Jaydan and his sister Micah, 5, bounded down the streets of Downtown Eastside in inner-city Vancouver.

The people hanging around those roads saw them and shouted to each other: “Kids on the block!”

Those who were using drugs started keeping their needles. Those who were fighting and swearing immediately quietened down.

But Jaydan’s eyes were sharp. He saw a needle packet discarded at the foot of a fence and pointed it out to his sister, who shrunk back in mock horror.

Later, the kids would tell the adults that they knew what the needles were used for—“to put poison into them”—and why people turned to them—“it makes them think about other things and nothing about the bad day.”

Jaydan and Micah are children of Craig Greenfield and his Cambodian-Chinese wife Nay, both 43. The parents were not afraid of bringing up their young children in the midst of drug addicts or former convicts. In return, the community was transformed by the presence of the children and altered their addictive behavior.

Sharing lives in Canada

Back in 2005, the family had moved into one of the poorest areas in Canada, where they began a radical social experiment by opening up their home to people struggling with homelessness, prostitution, and drug addiction.

Before moving to Canada, Craig had grown up in affluence in New Zealand. There, he had met his wife Nay, a refugee from the Khmer Rouge regime. After marrying, both of them had answered God’s call to serve and live alongside orphans in slums in Cambodia for seven years. They had made their home in two different slums there. Jaydan was conceived in one and raised in another, and Micah was also born in the second slum. Craig and Nay then felt led to apply what they had learned in the Asian slums to an urban area in an affluent, Western country.

While it seemed to be the exact opposite of where they had previously served, they saw that inner-city Vancouver had its share of physical and emotional poverty. There was rampant drug addiction, it had the highest Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection rate in the Western world, and four in five people lived alone.

“There are plenty of charities and soup kitchens there and people can get fed every half an hour. But such a charity model fosters a one-way relationship and a taking mentality,” says Craig. “We believe that people’s hurt and brokenness occurs in the context of relationships and often their families, and so healing and transformation will also come in the context of relationships—healthy ones.”

So, instead of handing out donuts in a charity line, he and his wife went to line up with everyone else to get the free donuts. As they got to know people, they invited them back to their home for meals or for a temporary roof over their heads. This was the basis of their Christian community, called Servants Vancouver which they founded.

The Greenfields now have two adjourning houses and two apartments. At any one time, they can house up to three families, four singles, and five children. “When people laugh together, do the dishes together, work together, play together, share lives together, we believe that there is something transformative about that,” says Craig.

In such a community, the children bring joy and companionship to the singles or drug addicts who have had their own children taken away from them. The adults are less inclined to indulge in addictive behaviors in front of the children, and become mentors to the young charges. “We want to practise radical hospitality, welcoming those who are not normally welcomed in this society, into our lives, into our homes, into our families,” says Craig.

One of the lives that was impacted by such a community was John, a former gang member who had been in and out of prison. He found a place where he was safe and able to stay clean from drugs, as well as a church family.

When asked if he was ever worried about his children being in such unusual company, Craig replies: “I would be more fearful bringing my children up in the midst of affluence and the kind of consumer society where they don’t get to mix with people of different socio-economic backgrounds and their only exposure to drugs is seeing Britney Spears and Paris Hilton on TV, glamorizing the drug using lifestyle.”

“My kids walk down the street and they see a guy lying there in the gutter like a down-and-out person, and they have no illusions on what drugs do to a person,” he adds.

The Greenfields continued to reach out to the drug addicts in the community for six years, giving them a place to detox and get back on their feet. Many of them needed a refuge while waiting to get into drug treatment centers, which had long waiting lists.

In 2012, a serious brush with cancer led Craig to think about what he wanted to spend his final years doing. Knowing that each of the men and women struggling with addiction, homelessness, or prostitution had started out life as a child longing for someone to love them, he decided to work with children, to try to address the problem at the roots.

So, in 2013, the family moved back to Cambodia, as they felt God’s leading to re-engage directly with the needs of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable children in the developing world.

(From left) Nay, Micah, Jaydan and Craig.

Convicted in Cambodia

It was a return to the place where Craig had first discovered the value of setting up a Christian community. His calling to the urban poor in Cambodia grew from a short-term mission trip in Phnom Penh which he did during a six-month break from university in New Zealand. Craig, who majored in commerce, had been raised in a Christian family who freely opened their doors to the vulnerable in society.

During the mission trip, young Craig befriended people who were dirt poor and homeless and were not interested in an abstract theology that seemed to be disengaged from their physical needs. “I am very poor. What can Jesus do for me?” one of them asked Craig.

Craig, then 22 years old, also remembered coming across a beggar outside a genocide museum. The beggar leaned on a wooden crutch and thrust an upturned baseball cap in his direction. A faded and filthy red T-shirt hung from his body, and on the front of the T-shirt were four huge, peeling block letters: “W.W.J.D.”

Those letters haunted the young man. “When I was growing up, those letters were etched into fluorescent green rubber wristbands sold in Christian bookstores or printed on the front covers of upbeat Teen Bibles. But I had never seen those letters on the tattered T-shirt of a beggar,” he says.

Shortly after graduation, Craig met Nay at a church gathering and married her. Nay knew that one day she would go back to her home country and help her people. Similarly, Craig remembered the first stirrings to fulfill the Great Commission in Cambodia that God had placed in his heart during the mission trip. After some deliberation, he quit his job as a corporate executive in a successful technology start-up, and both of them moved into an impoverished Cambodian slum community called Victory Creek in 2002. Their aim was to serve Jesus by serving those in the “distressing disguise of the poor”.

A two-room shack, barely tall enough to stand upright in, with only one window and one door to let light in, was their castle. Craig and May lived alongside the poor, listened to their concerns, and tried to meet their needs.

In their time there, they realized that many children were put in orphanages because their parents had either died from Aids or did not have the resources to raise their children. In his work with international humanitarian workers and consultants there, Craig learned that orphanage care could actually be harmful for the children. For instance, research has shown that institutional care has a negative effect on the psycho-social development of children. It also fosters a sense of disconnectedness, as the community is not involved in the care of the orphans.

Craig and Nay in Cambodia

Equipping locals in Cambodia

So Craig developed a ministry to help Cambodian communities care for their own orphans, and it eventually reached out to hundreds of vulnerable children and sparked a mentoring movement called Alongsiders International.

The basic concept of Alongsiders is getting extended family members or local volunteers to foster or mentor orphans in their midst.

“Cambodians have a proverb, ‘It takes a spider to repair its own web’. Our growing conviction as outsiders is to equip the locals or insiders to become alongsiders in journeying through life with the vulnerable in their society,” says Craig. He has seen orphans who had benefited from the love and support of others become “wounded healers” and extend the same love and support to others.

Today, the Alongsiders movement has spread into many provinces of Cambodia, as well as India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Myanmar, and beyond.

Craig and his family are still in Cambodia leading Alongsiders international, which now has thousands of young Christians making disciples in 15 countries. He says: “Mother Teresa once said that loneliness and the feeling of being unwanted is truly the most terrible poverty. Our mission is to train and guide young Christians in poor nations to walk alongside those who walk alone.”

Check out Craig’s latest book “The Alongsiders Story” or join the movement at www.alongsiders.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!